I’ve written earlier how I was moved to start blogging after becoming a reader of a blog by another revert to the Orthodox Church by the name of Mark, who fell asleep in the Lord this past January. There’s a lot of good information up at his blog still worth reading. This, I believe, is one of his best articles.

H/T: Central Pennsylvania Orthodox

Ah, so you’re going to a Byzantine liturgy. In the spirit of Frederica Mathewes-Green’s 12 Things I Wish I’d Known (with which I cannot, alas, compete), here are a few things that will make your visit more fruitful, and perhaps, a bit less uncomfortable.

What you’ll experience is utterly unlike anything you’ve encountered, and in not one, but many ways. I was completely befuddled the first time I attended a Divine Liturgy (partly because every syllable was Greek, but only partly). I want to make your experience a bit less stressful.

"Let my prayer be incense before you; my uplifted hands an evening sacrifice." Psalm 141:2

Incense!

There is no such thing as a Byzantine service without incense. Not just a little incense as the Romans use (on the rare occasions there is incense at all), but a lot of incense. Clouds of incense. Literally. You will be censed multiple times. Every icon in the church will be censed multiple times. Incense, incense, incense. Incense during Matins. Incense during Vespers. Incense during the Divine Liturgy. Incense, incense, incense, and more incense. If it bothers you, you’d best rethink going.

Shoes!

The first thing you need to know is this: No matter how ratty they may be, wear your most comfortable shoes. Don’t dress like a slob, but nobody cares what shoes you wear, and the reason is, as Mrs. Mathewes-Green so wittingly put it, “Stand up, stand up for Jesus.”

In the Orthodox tradition, the faithful stand up for nearly the entire service. Really. In some Orthodox churches, there won’t even be any chairs, except a few scattered at the edges of the room for those who need them. Expect variation in practice: some churches, especially those that bought already-existing church buildings, will have well-used pews. In any case, if you find the amount of standing too challenging you’re welcome to take a seat. No one minds or probably even notices. Long-term standing gets easier with practice.

What she does not tell you in this section (although she does address it) is that our services last for hours. Literally. Matins lasts a bit over an hour, longer if you’re attending a parish where people go to Confession on Sunday mornings (we usually go to Confession on Saturday evenings after Great Vespers, and during Great Lent, before the Liturgy of the Presanctified Gifts on Wednesday and Friday evenings), and Divine Liturgy will last a good hour and a half, and probably a bit longer, substantially longer if you’re attending on a Sunday during Great Lent when we use the Divine Liturgy of St Basil the Great. If you go at the beginning of Matins, you will be there for three hours, maybe a bit longer. (If it makes any difference, the Divine Liturgy begins when the priest chants, “Blessed is the Kingdom of the Father and the Son and the Holy Spirit, now and forever, and unto ages of ages” and the lights are turned on.)

If the church has pews and your feet are giving out, feel free to sit. If there are no pews in the church (my parish has no pews), there will be folding chairs, usually stacked against the walls. So if you go into the church and see those folding chairs, you may want to stand near the wall so you can grab one should you need it.

Because pews are a relatively recent Western innovation (most of those gothic cathedrals in Europe have no pews, or had them installed long after the cathedral was built) and never developed in the East, we have no pan-Orthodox rule on when you may sit, other than during the homily.

Kingdom of Heaven

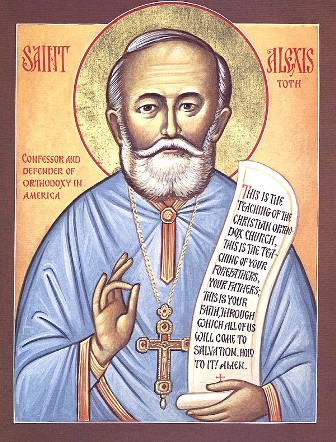

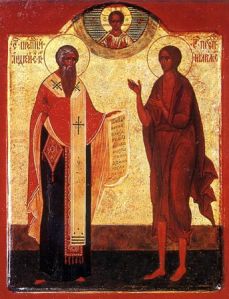

Byzantine worship is wholly theocentric. When we step over the threshold into the church, we leave this world behind us. The church represents the Kingdom of Heaven, so you are literally surrounded by icons, icons of Christ, icons of the Theotokos (the Mother of God), icons of the saints.

We love litanies, but we have no “customized” litanies as the Roman Catholics do (that may be one of those things that was never even mentioned in Vatican II, but slipped in). You will never hear the priest or deacon praying for “social justice” or whatever the currently popular euphemism for world Marxist government may be. Our feelings are irrelevant in church. We are there to worship God the Father, God the Son, and God the Holy Spirit.

To worship with us is to experience the timeless. There is a permeating, inescapable sense of ancient tradition, one that upon my initial encouter, left me shaken. We also rely far more on the Old Testament than do Western Christian traditions, not only for liturgical sources, but vestments and church architecture. There is nothing “modern” about Byzantine worship.

Why is everybody moving around?

Western and Eastern church behavior are wholly different. The church will list the times for Matins (Orthros) and the Divine Liturgy out front, which makes them seem like two distinct services, and they are, but one runs right into the other, with no break. So if you arrive at 10:20 for the Divine Liturgy at 10:30, you will not walk into a quiet church of people waiting for the liturgy to begin, but a church well into worship, somewhere toward the end of Matins.

This makes Westerners uncomfortable, but it shouldn’t. The faithful trickle in, starting before Matins to after the Divine Liturgy begins. Nobody will think you got there late.

Ah, the trickling in. After you arrive, you will notice that some people are standing and worshipping while those who come in are bowing, crossing themselves, lighting candles and placing them before icons, crossing themselves, bowing, and so forth as they go from icon to icon throughout the church, all while the worship service is going on. This is the way it’s done, and typically, those icons and stands of candles are up at the front of the church and not in the rear. As we enter the church, we perform our private devotions, and eventually, as you will see, we join the congregation in worship. The Western equivalent is how Roman Catholics will genuflect then kneel and pray, even when they arrive late, so it really is the same thing, but it does seem unsettling to many Western Christians. The general rule, by the way, is this: If the priest or deacon is in the nave, on this side of the iconostasis, do not go forward to venerate the icons; instead, wait until the priest and deacon are in the sanctuary, behind the iconostasis.

By the way, genuflection is unknown in Eastern Christianity. We cross ourselves or do metanias when we enter the church, or when we cross the center of the church, as Roman Catholics genuflect and cross themselves, and for the same reasons (you can’t see the tabernacle because it’s behind the iconostasis, but it’s there). But we don’t genuflect, not even during Great Lent, and that leads us to our next topic.

One thing that should relieve Protestants

We don’t kneel. Usually.

During Great Lent, however, we do prostrations, not as the Roman Catholics do them at ordinations, lie fully face down, but just as the Muslims do (where do you think Mohammed got it?) We kneel, place our hands down on the floor and touch our forehead to the floor between them. Feel no pressure to follow along. If you want to do something, feel free to bow or kneel.

Actually, I wouldn’t advise that you visit during the first week of Great Lent, at least not when we are chanting the Great Canon of St Andrew of Crete. We do prostrations and immediately return to our feet approximately 120 times during one service, and it’s quite a workout. Your thighs will shake from weakess at the end. We do full prostrations during the Liturgy of the Presanctified Gifts on Wednesdays and Fridays during Great Lent, but we stay down, and it’s not strenuous.

If you attend a Divine Liturgy on a weekday (except for the period between Pascha and Pentecost), we do full prostrations during the Lord’s Prayer, after the Epiklesis (“Again we offer unto Thee this reasonable and bloodless worship, and we ask Thee, and pray Thee, and supplicate Thee: Send down Thy Holy Spirit upon us and upon these gifts here offered. And make this bread the precious Body of Thy Christ. Amen. And that which is in this cup, the precious Blood of Thy Christ. Amen. Making the change by the Holy Spirit. Amen, Amen, Amen”) and during the Communion Prayer (“I believe, O Lord, and I confess that Thou art truly the Christ, the Son of the Living God …”)

What do I do?

Protestants always wonder what they should do at a Roman Catholic Mass, and the same ten times over at an Orthodox liturgy. Roman Catholics also wonder what they should do at an Orthodox or Eastern Rite liturgy. Relax. Assuming you’re in the United States, if you look around, you will notice that people aren’t doing the same things at the same times, something Roman Catholics find unsettling.

Different traditions have developed similar, but slightly different customs, and except in larger cities where there are large enough ethnic communities to support several churches, American parishes tend to be pan-ethnic, and therefore, pan-tradition. Those from a Greek Orthodox background won’t necessarily be doing exactly the same thing at the same time as those from a Carpatho-Russian background, and they in turn won’t necessarily be doing the same thing at the same time as those from a Russian background, and so it goes.

If you’re a stickler, we cross ourselves from right to left (push, not pull), often three times (although that differs from tradition to tradition), and always with the thumb and first two fingers touching (for the Three Persons of the Trinity), and the two remaining fingers touching the palm (for the Two Natures of Christ, touching the palm to represent Christ descending to Earth). Nobody, however, is going to inspect to make sure your fingers are in the right places. Again, relax. We cross ourselves far, far more than do Roman Catholics.

If you’re Roman Catholic or Anglican and you cross yourself from left to right, nobody cares, and chances are nobody will even notice. Uniformity just doesn’t exist in Byzantine Christianity as it does in the West. We are glad to have you worship with us, no matter what your background, and nobody is there to catch you doing something “wrong.” If you choose to stand and just take it in, that’s fine. If you want to participate as best you can, that’s fine, too, as long as you know beforehand that not all parishes have service books (most do, but not all). In my experience, most Orthodox service books aren’t as complete as they could be, often using abbreviations (I suspect they are more for visiting Orthodox from different traditions because we all use different translations, more than you). If it’s only your first or second time, I would suggest that instead of trying to follow along, you listen and pray (more about that below).

What is this, a gym?

Byzantine worship is more “physical” than Western liturgical traditions. In addition to crossing ourselves many, many times, and the full prostrations mentioned above, we perform bows and the metania.

The metania is when we cross ourselves, then bow at the waist and let our right hand drop so that our fingers brush the ground, then rise. Metanias are more frequent in Russian custom than Greek (remember the discussion about differing customs): Those from a Byzantine tradition church (Greek and Antiochian Orthodox) will typically cross themselves before reverencing an icon, while those from a Slavic tradition church (OCA, ROCOR, Carpatho-Russian, Ukranian, etc.) will typically perform the metania, two before reverencing the icon, and one after, or even perform full prostrations, but even that isn’t entirely uniform, and there are differences within those two broad groups. One place, however, where the metania is near universal is during the call to worship, and is performed at every verse:

+O come let us worship God our King!

+O come let us worship and fall down before Christ our King and our God!

+O Come let us worship and fall down before Christ Himself our King and our God!

The metania is also done at the Trisagion (“Holy God, Holy Mighty, Holy Immortal, have mercy on us”), at every recitation of “Alleluia, alleluia, alleluia, glory to Thee, O God,” and “Blessed art Thou O Lord, teach me Thy statutes.” It is also done on Sundays when a full prostration would be done on a weekday Liturgy, such as during the Lord’s Prayer, the Epiklesis, and the Communion Prayer.

We bow (incline our heads and bend forward) when we are censed, when we are blessed by the priest, and when the priest bows to us asking our forgiveness. Like Roman Catholics, we cross ourselves at every mention of the Three Persons of the Trinity. One place where we do not cross ourselves is when the priest makes the Sign of the Cross over us.

That filioque clause!

If you’re Roman Catholic, Anglican, or Lutheran, that is, a Westerner who is familiar with the Nicene Creed, you absolutely need to know this: We say “who proceeds from the Father,” and emphatically not, “who proceeds from the Father and the Son.” The “and the Son” is the filioque clause (Latin for “and the Son”), inserted hundreds of years after the First Nicene Council, and is a particular bone of contention between East and West. Or perhaps I should say the West doesn’t consider it an issue, but the East takes it very seriously. To make it even more confusing, some Eastern Rite churches (all in communion with Rome) insert it, while others do not. No Orthodox church, however, inserts it, so if you say it, you’ll be the only person in the church saying it (our parish chants the Creed).

If it makes you feel any better, because different traditions use different translations, even we are tripped up from time to time (just not on that one little clause). I still fall into the translation used by my home Antiochian parish and “goof” in my OCA parish here. No big deal.

While we’re on those things that you could be saying all by yourself accidentally, like Roman Catholics, we pray the Lord’s Prayer only up to the Doxology, which the priest chants alone. Debts, debtors, trespasses, trespass against us? It depends on the parish and what translation they use.

Music?

Byzantine Christianity has no hymnology as it developed in the West; there aren’t even Christmas carols on Christmas. We do have hymns, but specific hymns appear at specific places, that is, they are prescribed by the Church, and cannot be “chosen” by the choir director.

In most parishes, everything is chanted. Different parishes have different musical traditions, and different levels of participation. Greek and Antiochian churches (Byzantine tradition) typically say the Creed and Lord’s Prayer, while OCA, Carpatho-Russian, ROCOR, and other Slavic tradition churches chant them, but there are exceptions. If you go to a Slavic church (that includes the OCA), there will surely be a choir, and the polyphonic music will sound familiar to your Western ears. If you go to a Greek church, there may only be a chanter or two, and the chant will sound exotic (even more so if you go to an Antiochian parish that uses Syrian chant). In my OCA parish, Slavic, but still a typical Heinz 57 American parish, you hear chanters and Byzantine chant during Matins up to the very end, The Great Doxology, when the choir takes over, and the music becomes (mostly) Slavic.

Because Slavic chant is so accessible to Western ears, it has spread beyond Slavic parishes, and in an American parish, even in an Antiochian parish, you’re likely to encounter it.

Although there are a few Orthodox churches that introduced organs, instrumental music is a Western innovation. Expect everything to be a cappella.

Holy Communion

If you aren’t Orthodox, please do not approach for Holy Communion. If you are Orthodox, but unknown to the priest, please do not approach for Holy Communion (then, if you’re Orthodox, you already know that).

Eastern Christianity has no “impersonal” Sacraments, as have developed in the West. We have no confessionals, but confess next to the priest at the front of the church (yes, in front of everybody else). A chanter will be chanting the Psalms during confessions, so nothing is overheard. When we commune, the priest addresses us by our Christian name, “The servant/handmaiden of God, NAME” as he does when he absolves us. Holy Communion is intensely personal, and contrasts starkly with the “assembly line” Eucharist in large, Western churches.

Eastern priests, whether Orthodox or Eastern Rite, are guardians of the Chalice. Roman Catholic priests are, at least traditionally, but because of the huge sizes of parishes and the impersonal nature of the Sacrament, cannot fulfill that role as Eastern priests do. If you go to Holy Communion and the priest has no idea who you are, he is likely to bless you, and allow you to kiss the foot of the Chalice, but is very unlikely to give you Holy Communion. That’s why at the beginning I said not to go to Holy Communion in a strange parish without speaking first to the priest.

You may be startled to see parents with infants in their arms in the line, and even more startled to see that the priest communes the infants. We practice full-immersion infant baptism, and immediately after baptism, the child is chrismated (confirmed). All baptized and chrismated Orthodox (or in the case of Eastern Rite, Catholics) may commune, including infants, and baptism is a child’s First Communion.

If you are Roman Catholic and attending an Eastern Rite liturgy, you may commune, but please introduce yourself to the priest first, and if you’ve never communed in a Byzantine church before, do your homework first. It is definitely very different from communing in a Roman Catholic parish.

We tend to commune less frequently than Western Christians, although people are communing more frequently than they used to, largely due to the large number of converts from Western Christian traditions (in our parish on any given Sunday, I’d approximate that about half commune). Still, not communing is less likely to make you feel “left out” than it might in a Roman Catholic or Anglican service.

Let us complete our prayer unto the Lord . . .

The end is near? Don’t you believe it! The liturgy will continue about fifteen minutes after Holy Communion, longer in a Greek parish where the custom is for the homily to be at the end, rather than after the Gospel. At the end, we go to the front to kiss the cross (on the feet of Christ) and take the priest’s blessing, and you will notice people taking a bit of bread. This is the antidoron, not the Body of Christ (although it is blessed, and is cut from the same loaf), and everyone is welcome to a piece of blessed bread. If you are uncomfortable and do not want to approach the priest at the end, that’s fine, and you may find that the person standing next to you brings you back a piece of bread. Just know that you are as welcome as anyone to receive the priest’s blessing and take a piece of bread.

We use leavened bread to symbolize the risen Christ.

The end, especially for Protestants

Like the Roman Catholics, we never developed the practice of the priest standing at the door greeting people as they left (although I do think it’s an excellent custom, and at the end, the priest will often speak briefly to each parishioner). Because we fast from sundown on Saturday until Holy Communion (or are supposed to), many parishes meet somewhere near, often in the basement or a parish hall, and break the fast after the liturgy, or at least have their first coffee of the day (better get in line as soon as you get there, because the coffee goes fast). Many Protestants do the same. Please feel free to join us. And I’m not directing the invitation especially to Protestants. That referred to the clergyman greeting people as they left the church.

Lex orandi, lex credendi

Literally, “The law of prayer [is the] law of belief,” loosely translated, it means “As we pray, so we believe.” It is, if anything, even more fundamentally true of Byzantine worship than even Roman Catholic or Anglican (although the same principle applies there). When we worship, we are expressing the fullness of our faith.

There are thousands of Orthodox theologians, from the Church Fathers to Fathers Lossky and Schmemman, and if you’re curious, you could spend the rest of your life reading treatises on theology. But here’s the thing: You don’t have to.

Instead of focusing on all of the strangeness and difference going on around you, listen. Pay close attention to what is being chanted. You can worship with us without bowing and crossing yourself constantly by listening and praying with us. And if you listen, you don’t have to ask us what we believe. You are hearing it.

And please come back!

Example of translation differences. The communion prayer from the Divine Liturgy.

|

Antiochian:

|

OCA:

|

| I believe, O Lord, and I confess that Thou art truly the Christ, the Son of the living God, Who didst come into the world to save sinners, of whom I am chief. And I believe that this is truly Thine own immaculate Body, and that this is truly Thine own precious Blood. Wherefore I pray Thee, have mercy upon me and forgive my transgressions both voluntary and involuntary, of word and of deed, of knowledge and of ignorance; and make me worthy to partake without condemnation of Thine immaculate Mysteries, unto remission of my sins and unto life everlasting. Amen |

I believe, O Lord, and I confess that Thou art truly the Christ, the Son of the Living God, Who camest into the world to save sinners, of whom I am first. I believe also that this is truly Thine own pure Body, and that this is truly Thine own precious Blood. Therefore I pray Thee: have mercy upon me and forgive my transgressions both voluntary and involuntary, of word and of deed, of knowledge and of ignorance. And make me worthy to partake without condemnation of Thy most pure Mysteries, for the remission of my sins, and unto life everlasting. Amen. |

| Of Thy Mystical Supper, O Son of God, accept me today as a communicant, for I will not speak of Thy Mystery to Thine enemies, neither will I give Thee a kiss as did Judas; but like the thief will I confess Thee: Remember me, O Lord, in Thy Kingdom. |

Of Thy Mystical Supper, O Son of God, accept me today as a communicant; for I will not speak of Thy Mystery to Thine enemies, neither like Judas will I give Thee a kiss; but like the thief will I confess Thee: Remember me, O Lord in Thy Kingdom. Amen. |

| Not unto judgment nor unto condemnation be my partaking of Thy Holy Mysteries, O Lord, but unto the healing of soul and body. |

May the communion of Thy Holy Mysteries be neither to my judgment, nor to my condemnation, O Lord, but to the healing of soul and body. Amen. |

Posted by orthocath

Posted by orthocath